What the Supreme Court’s Landmark Decision on Affirmative Action Means for Pay Equity and D&I

As compensation professionals, we’re impacted by a broad array of regulation and public policy. The path to our desks typically goes through rulemaking by the SEC, legislation from Congress, and executive orders by the president. But now and then, something lands from the nation’s highest court as well.

On June 29, the United States Supreme Court ruled on Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and its companion case, Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina et al. Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) is a nonprofit member-based organization that litigates cases about the use of race in university admissions decisions. In this landmark decision, the Supreme Court ruled 6-2 that admission practices relating to the use of race are unlawful under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.[1]

While the Supreme Court’s decision doesn’t deal directly with corporate America, its ruling set off major reverberations for diversity and inclusion (D&I) and pay equity. Some companies may need to change aspects of their programs in these areas, and others may not. We contend that broader principles of doing the right thing in a class-agnostic manner remain possible. At the same time, SFFA is a flashpoint that companies need to understand and steer clear of.

We’ll lay the foundation with a brief overview of the Supreme Court’s reasoning. Then we’ll tie the court’s reasoning back to contemporary corporate pay equity and D&I initiatives. In doing so, we’ll highlight ways that some efforts can increase litigation exposure and steps organizations can take to achieve their dual objectives of abiding by the law and advancing their human capital strategies.

What did the Supreme Court decide?

This case originated in 2013 when SFFA filed suit against Harvard alleging that its undergraduate admission practices violated Title VI by discriminating against Asian Americans in favor of some other races, implicitly making admissions criteria different for students of different races. Lower courts initially upheld Harvard’s limited use of race as a factor in admissions. Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, declared that affirmative action in college admissions is unconstitutional.

The majority opinion leans on the Equal Protection Clause, which prohibits governmentally imposed discrimination based on race because the law should be the same for all persons, regardless of race. While exceptions may exist, a standard called “strict scrutiny” is used to assess the constitutionality of any such exceptions. Strict scrutiny poses a two-step test. First, is there a compelling state interest? Second, is the action narrowly tailored and necessary to achieve that interest?

In his opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts argues extensively that race-conscious admissions policies fall far short of meeting the strict scrutiny test. Goal measurability and an indefinite timeframe are among the top concerns. As we think about corporate topics of pay equity and D&I initiatives, SFFA reflects a great deal of skepticism that exceptions made today will be unwound tomorrow.

The Supreme Court’s decision also draws reference to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which is a federal statute prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. Both Title VI and the Equal Protection Clause aim to prevent discrimination, but operate in different legal domains and address different entities.

How does SFFA tie to corporate policy and decision-making?

The Equal Protection Clause applies to public institutions, which describes the University of North Carolina but not Harvard. Harvard, however, does fall under the purview of Title VI because it receives federal funding. The Supreme Court applied its interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause to Harvard via Title VI.

Private companies who are contractors to the federal government, or work on federally funded projects, arguably are subject to Title VI. Given the logic in the Supreme Court’s decision, this entails a cross-link back to the Equal Protection Clause. Although we’re not constitutional law experts and what follows is not veiled legal advice, our hunch is that even private companies with no link to federal funding could still get pulled into the issues that SFFA raises.

One way this happens is through Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which deals directly with employment using (obviously) analogous principles. As many of our lawyer friends have explained to us, a common defense against a Title VII discrimination claim is that the action was being taken pursuant to an affirmative action policy. It stands to reason that this affirmative defense may be weakened or even eliminated as a result of SFFA.

Another potential risk for corporations is litigation from employees or even activist shareholders alleging unfair pay, hiring, promotion, or termination practices resulting from the company’s D&I initiatives. (More on this later.)

In summary, it’s hard to imagine a scenario in which SFFA isn’t applied to corporate contexts. While we appreciate the diverse viewpoints on this landmark decision, we think it’s quite possible to advance important human capital priorities without tripping over the Supreme Court’s newly created precedents.

Do pay equity programs clash with SFFA?

No, they shouldn’t. But first we need to define what pay equity is.

In the US, pay equity is generally understood to mean equal pay for substantially similar work. Pay will naturally vary from person to person based on role, performance, experience, location, or any number of other appropriate factors. But it shouldn’t differ based on gender, race, or other protected categories. When pay equity exists, pay differences aren’t linked to invalid drivers of pay. (For more, be sure to peruse our e-book on pay equity.)

Done right, pay equity studies use multivariate regression to control for differences in role and other factors. The output of a pay equity study is called the adjusted pay gap, because valid drivers of pay are adjusted for in the underlying assessment.

We’ve seen a vast array of programs, approaches, and tools for managing pay equity. A cottage industry of solutions providers has also emerged due to the rise of ESG topics and, as is customary in any high-growth space, levels of quality and effectiveness vary. In our view, many would never hold up in litigation.

Outside the US, and even in certain states within the US, legislation has required reporting what are called “unadjusted” pay differences between men and women. These calculations fail to account for differences in role, tenure, location, education, etc. They look at the average or median pay by gender or ethnicity, which often reveals sizable differences, but mostly due to representation. (Think female-dominated, lower-paying jobs like bank teller and male-dominated, higher-paying jobs like commercial banker.) Although important, the unadjusted pay gap is not a measure of equal pay for substantially similar work.

In this regard, a pay equity study is perfectly consistent with the Supreme Court’s decision. Both Title VI and the Equal Protection Clause focus on race, but we think they’re easily analogized to gender or any other comparable category. A pay equity study tests whether there’s evidence of pay disparity driven by someone’s race or gender. The underlying premise is that pay should be fully and exhaustively explained by valid factors—such as role, location, performance, or tenure—and not depend on invalid factors like gender or race. Besides being good corporate policy, this is simply the law (as per the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and, of course, Title VII).

Are there ways in which pay equity programs can clash with the Supreme Court’s decision?

Yes.

We always worry about poorly specified analyses frameworks that lead to incorrect conclusions. But this isn’t really what the Supreme Court’s decision is about—flawed analysis frameworks have and will continue to be one angle in litigation. We’re much more concerned about the way companies approach remediation efforts.

The most basic output of a pay equity study is the adjusted pay gap, usually expressed as the ratio of pay difference between the categories tested. For example, a conclusion may be that women earn 99% of what men earn (after holding all parameters such as role, tenure, and performance constant), which means there’s a 1% adjusted pay gap in favor of male employees.[2] After determining the adjusted pay gap, an analysis is performed as to what’s behind the gap. The analysis includes a list of the outlier employees, with an eye toward negative outliers (employees whose actual pay is far below the level predicted by the model). The outlier group will include people of both genders and all races, though when there’s a wide gap it’s likely that the outlier group will be more heavily represented by the disadvantaged group.

After forensically examining the outliers to make sure there are not valid reasons for their pay that the model doesn’t capture, companies often adjust the compensation of outlier employees to resolve the situation. There are many ways of doing this. Some companies choose to adjust pay only for employees in disadvantaged groups, such as outlier females.

Another question is how much to adjust the pay of outliers. For example, you can adjust them upward merely to the point in which they’re no longer statistical outliers, or all the way to the pay level predicted by the model. The latter means those employees may leapfrog comparable non-outlier employees whose pay isn’t being similarly adjusted.

We’re most worried about remediation efforts that aren’t blind to gender and race. If the regression model identifies a person of color (POC) and non-POC as outliers, and both have identical qualities, any action that treats them differently simply based on their race is a concern. The Supreme Court’s analysis in SFFA would suggest the two outlier individuals should be treated identically, or at least any differential treatment must not be linked back to gender or race.

This is how we’ve always approached our pay equity projects, but we’ve heard there are diverging practices in the community. We’re aware of some companies using off-the-shelf software wherein it might not be entirely clear what the tool is doing or how it’s arriving at its conclusions. Now is a key time to bone up on the methodology and its appropriateness.

How about D&I initiatives?

We differentiate D&I initiatives from pay equity because pay equity is very focused and targeted in the question it’s trying to answer. Namely, is there any evidence of people performing substantially similar work being paid differently? In contrast, diversity and inclusion efforts run the gamut.

Some D&I initiatives address the cause while others address the symptom. If the problem is that there aren’t enough female engineers, the cause arguably links back to messages and opportunities that arise in elementary school and onward. The symptom is that very few females apply to technology jobs because very few graduate from computer science programs. The terminal symptom is that companies may lose the female engineers they do hire at unacceptable rates (with the reasons for this varying by situation).

The riskiest D&I initiatives are those that enable the selection or prioritization of an employee or recruiting candidate based on their gender or race. Risk is amplified when it comes to decisions about things like pay, hiring, promotion, and firing. That is, someone needs to assert that they were harmed in their compensation, pursuit of employment, pursuit of promotion, or termination.

One case that’s made headlines is DiBenedetto v. AT&T. The plaintiff, a 58-year-old white male, alleges that his termination was a result of AT&T’s corporate diversity priorities. Absent those initiatives, according to the complaint, he wouldn’t have been terminated and may have even been promoted when his former boss retired.

An example of a D&I program that probably wouldn’t create any complications, even if the vast majority of participants are female, is a resource group or mentoring program for employees reentering the workforce. Employee resource groups and mentoring programs are examples that, on their face, appear quite different. Even so, the internal documentation and language used to discuss these initiatives matters, and should be prepared with an understanding of what the law does and doesn’t permit.

Are there other associated D&I risks?

Yes. Public disclosure.

Companies will launch hundreds of programs and initiatives to support a diverse employee base. It seems inevitable that someone is terminated or passed up for promotion and blames it on some corporate policy. One place both a plaintiff and the court will turn to is what the company has stated its intentions to be, and the first place to look is public disclosure.

In 2020, the SEC adopted Release No. 33-10825, Modernization of Regulation S-K Items 101, 103, and 105. Our interest here is in the revision to Item 101(c), which focuses on how an organization manages its human capital. The rule is principles-based and therefore very brief. But in summary, it requires companies to discuss their human capital management strategy, including the metrics they use for measurement and monitoring. Importantly, this disclosure occurs on the face of the 10-K.

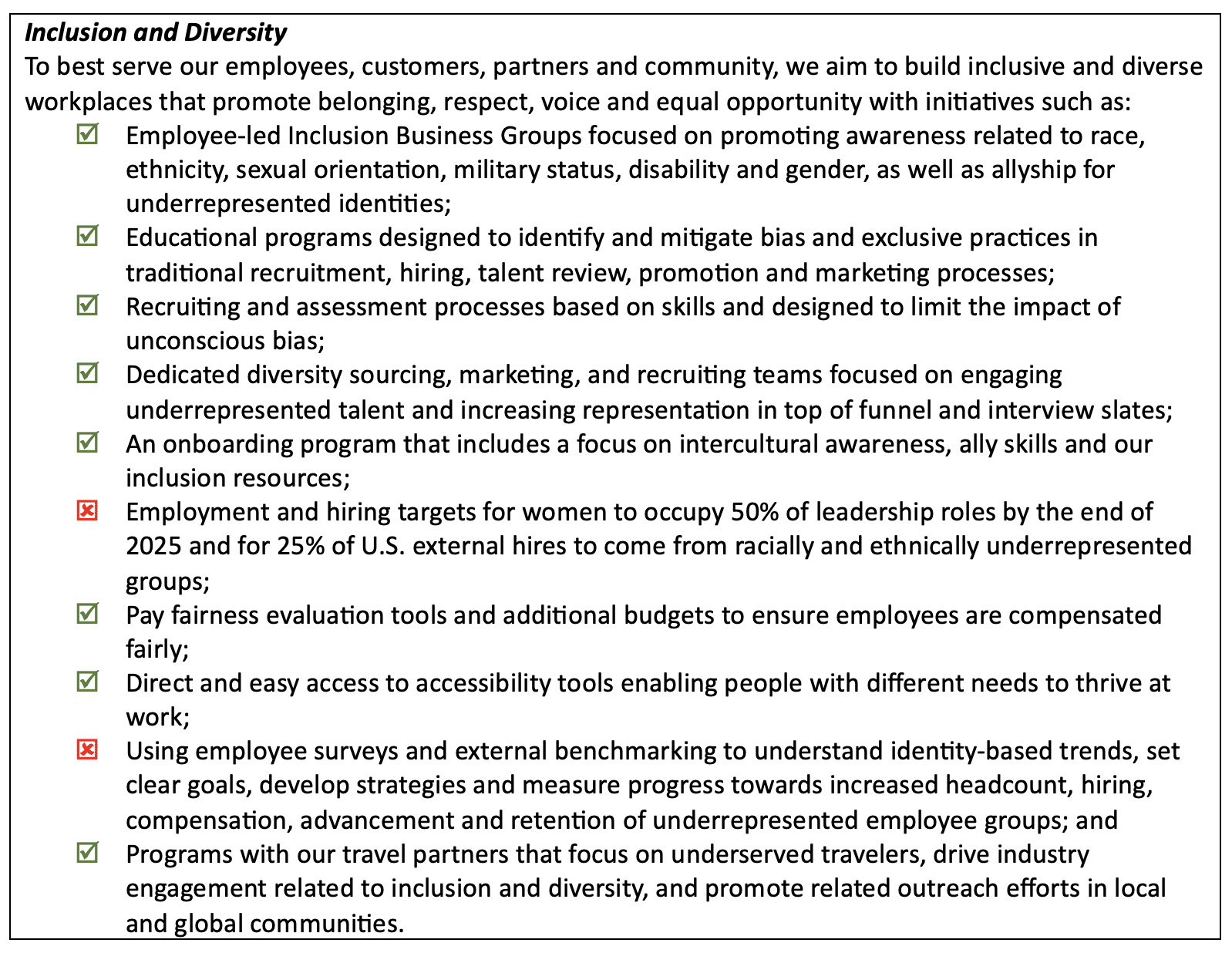

Let’s look at a section of Expedia Group’s 2023 10-K disclosure. We replaced the bullets in the actual disclosure with a green checkmark or red X. The latter denotes initiatives that could be used as fodder in litigation that dovetails with SFFA topics.

Unsurprisingly, there’s been an uptick in litigation related to hiring, firing, and promotion decisions being linked to race or gender. For example, in Powers v. Broken Hill Proprietary, the plaintiff is a man who worked for Broken Hill Proprietary USA, an Australian mining and metals company with a large presence in Houston. The plaintiff argues that his termination

was the direct result of BHP’s publicly announced decision from its parent’s headquarters in Australia to purposefully systemically discriminate in favor of females (and against males), on a global basis, so that it can achieve a 50% female workforce by 2025, from 17% in 2015… To achieve that corporate-wide mandate, BHP uses bonuses tied to specific sex-based targets to motivate its managers to make personnel decisions based on sex.

The case ultimately settled, but the company’s D&I targets were strategically emphasized at the very beginning of the complaint.

We’re not litigators, and this is a topic where our litigator friends are far away from a consensus viewpoint. Some have suggested the two X cases are fine because they’re goals, not quotas. Others say it may not be a smoking gun but amps up the risk. Just keep in mind that the first place a crafty plaintiff’s litigator is going to look at is information that’s been loudly and visibly disclosed externally. That includes the 10-K, proxy, corporate social responsibility report, and company website.

Where does incentive design come in?

As you probably noticed in the above quote, the plaintiff in Powers also latched on to the organization’s diversity goals in its bonus programs. If executives are going to get paid based on achieving particular D&I goals, these goals will undoubtedly come up in any litigation alleging unfair discrimination in hiring, firing, or promotion.

We’re not advising against the use of these goals. The obvious defense is that any incentive metric can backfire. An EBITDA margin metric can drive reckless cost-cutting. A revenue growth metric can motivate diversification for the sake of empire building. The list goes on and on. The mere existence of an incentive or goal that has a dark side to it does not create causation for that path to be acted upon.

In other words, even though the front page of a complaint may focus on D&I goals and incentive metrics, the case will ultimately come down to the organization’s actual policies and practices for making decisions. This is a good thing as we know companies are intently focused on constantly refining and upgrading their internal protocols.

Action items and wrap-up

The Supreme Court’s decision in SFFA has implications that extend well beyond the walls of academic institutions. We approach this topic apolitically. In our experience, corporations usually work hard to do the right thing. They’re trying to widen their human capital pipelines so they can attract and retain the strongest workforce possible. Business is hard and talent excellence is at the root of every strategy.

Litigation over human capital matters can be paralyzing. We look at SFFA simply as a North Star as to how the risk vector is evolving. Where a company wishes to be on that vector depends on a host of factors that are company specific.

Here are our suggestions and takeaways:

- In collaboration with legal counsel, develop your own interpretation of how SFFA is likely to influence Title VII and related litigation. We shared some of our predictions here, but this is obviously an evolving and nuanced area, and it’s important that each company form its own point of view

- Socialize that point of view with executives, HR business partners, and business line leaders

- Review all internal documentation and policy material to ensure compliance

- Review the current pay equity management approach to ensure compliance. If working with consultants like us, talk to them about what the models are doing and the assumptions they make. If using software, be extra critical (we can review and pressure-test what software is doing)

- Conduct a comprehensive analysis of all D&I initiatives to assess how they interact with SFFA and your company’s position

- If using forward-looking D&I targets or D&I goals in an incentive plan, consider the cost-benefit implications

- Carefully review all disclosure in the 10-K, CSR report, proxy, website, and other external-facing communications

- Conduct adverse impact analyses of hiring, termination, and promotion decisions (using much of the same econometric modeling as a pay equity analysis)

The good news is that nothing in SFFA is stopping a company from continuing to pursue bold, creative strategies to develop and retain a diverse workforce. What matters the most—what always will matter the most—are the specific policies, programs, and initiatives to widen the human capital pipeline and retain superior talent in a bias-free environment.

[1] Since there are technically two cases the Supreme Court ruled on, one against Harvard and one against the University of North Carolina, we’ll refer to the decision collectively as SFFA (i.e., the plaintiff in both).

[2] This approach is different from the commonly quoted statistics in the news, which typically are unadjusted pay gaps that do not hold all parameters constant.